Monday, May 31, 2010

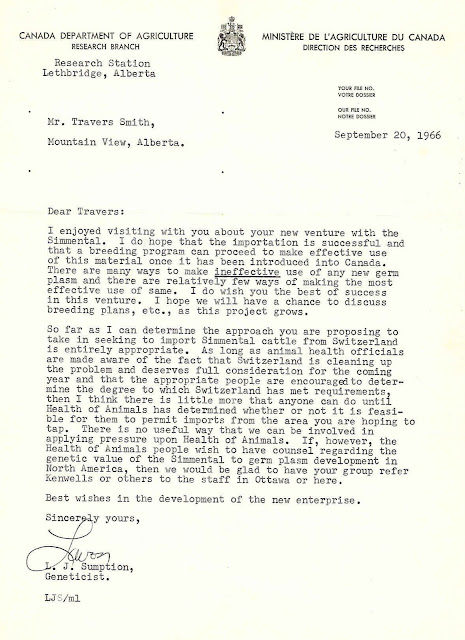

1.14: Push to Open Switzerland

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

Travers had been so impressed with the cattle in Switzerland that upon his return to Canada in mid-August, he immediately set about keeping in touch with the Canadian government by telephone and correspondence, pressing for similar export allowances for Switzerland that had been granted to France. Travers sought support wherever he could. In the meantime, on faith and hope, he proceeded to direct cattle selection in Switzerland through his two Swiss contacts, trusting in their expertise and trusting that the Canadian government would come through to open Switzerland for the coming import year of 1967-68.

Travers had been so impressed with the cattle in Switzerland that upon his return to Canada in mid-August, he immediately set about keeping in touch with the Canadian government by telephone and correspondence, pressing for similar export allowances for Switzerland that had been granted to France. Travers sought support wherever he could. In the meantime, on faith and hope, he proceeded to direct cattle selection in Switzerland through his two Swiss contacts, trusting in their expertise and trusting that the Canadian government would come through to open Switzerland for the coming import year of 1967-68.

Saturday, May 29, 2010

1:13: SBL (Simmental Breeders Limited)

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

Another priority that summer and fall of 1966 was to organize the group of local investors who had responded to Travers' enthusiasm as he described what he envisioned the Simmental breed could do to increase productivity, performance, and profitability in their livestock operations. By August 1966, seven men had committed to help Travers finance this venture that had so captured Travers' focus. On August 30, six of the eight initial contributors of capital met to determine the type of organization they would establish to transact the future business of the contributing group. Those present at the meeting were:

B. Travers Smith; Dr. Orson T. Bingham; Harold Watson; Guy Bowlby; H.J. Blackmore*; B.Y. Williams

Those absent were: Dr. S. B. Williams; Franklyn Smith

Each contributor's investment was $500.00 in cash with a further $500.00 guarantee to the bank for a $4,000.00 loan.

The name of the company was determined to be Simmental Breeders Limited,1 and direction was given for its incorporation which took place on September 26, 1966.

Chairman: B. Travers Smith

Secretary; B.Y. Williams

Dr. Orson T. Bingham was a Cardston dentist who ran cattle on the side.

Harold Watson was a rancher with some farming interests who lived at Mt. View and was brother-in-law to Travers Smith.

Guy Bowlby was a rancher living at Twin Butte, AB.*J.H. (James Horn) Blackmore (aka-Hastings James or H.J.) was a cattle rancher based in Leavitt & Mountain View

B.Y. Williams was manager of the Cardston Credit Union and rancher.

Dr. S.B. Williams was a Cardston dentist, with cattle interests on the side.

Frank Smith was a cattle rancher at Mt. View, AB, and brother to Travers.

There were others that Travers invited to join the venture, but who, for various reasons, were not ready, willing, or able to take the risks that certainly attended such an investment. This new breed of cattle was essentially unheard of in North America. For some, the performance facts of Simmental seemed to-good-to-be-true. If the Simmental were so good, why hadn't someone found a way to get them in long ago? The fact they were not in North America when their reputation for quality and performance were so widely and anciently recognized throughout the rest of the world was amazing to Travers, too. It seemed impossible that no one had found a way to get them here.

The first SBL logo was adopted about 1970.

(Phone and address are not longer valid as company no longer exists.)

---------/

1. On 25 July 1969 the company's name was changed to Simmental Breeders Cardston Limited, but it would always be known as SBL. (Ref.: Alberta corporate registry search).

Friday, May 28, 2010

1:12: Home Work

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

Upon arriving home, on Monday, August 15, Travers agenda was more than full. Many arrangements needed to be made, but the way was incredibly smoothed through the Canadian Charolais Association (CCA). That well-organized Association, at the request of the Canadian Department of Agriculture (CDA), took up the role of agent for all the Canadians importing from France. This involved arranging insurance and handling all matters of the Brest quarantine; chartering the ship from France to Grosse-Île; from Grosse-Île to Quebec City; and the transport thereafter by train to the West. Thus Parisien came under the well-organized, experienced Charolais umbrella, moving like clock-work from one stage of testing and quarantine to the next.

Upon arriving home, on Monday, August 15, Travers agenda was more than full. Many arrangements needed to be made, but the way was incredibly smoothed through the Canadian Charolais Association (CCA). That well-organized Association, at the request of the Canadian Department of Agriculture (CDA), took up the role of agent for all the Canadians importing from France. This involved arranging insurance and handling all matters of the Brest quarantine; chartering the ship from France to Grosse-Île; from Grosse-Île to Quebec City; and the transport thereafter by train to the West. Thus Parisien came under the well-organized, experienced Charolais umbrella, moving like clock-work from one stage of testing and quarantine to the next.

The CCA labors left Travers free to concentrate on other urgent matters.

(Below are two of several letters that Travers received from the CCA in making the many arrangements. The second letter is undated, but was probabaly written in mid- to late September 1966.)

Thursday, May 27, 2010

1.11: Return to Switzerland (August 7-12, 1966)

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

With the finding of Parisien, Travers' main mission was now accomplished, but he was still full of his Swiss dreams. He needed more time in Switzerland. He missed his Saturday night train to Berne, so he left Paris for Berne on Sunday morning, August 7, arriving in time to attend his evening religious services in the same chapel he had attended one week previous.

The week of August 8-12 was spent in Switzerland. Travers wrote that he spent his time

1. "Selecting the First Canadian Simmentals," by Travers Smith, Simmemtal Shield, October 1970, pp. 8-10, quote from page 9.

With the finding of Parisien, Travers' main mission was now accomplished, but he was still full of his Swiss dreams. He needed more time in Switzerland. He missed his Saturday night train to Berne, so he left Paris for Berne on Sunday morning, August 7, arriving in time to attend his evening religious services in the same chapel he had attended one week previous.

The week of August 8-12 was spent in Switzerland. Travers wrote that he spent his time

… making arrangements for the future, contacting all the government and export people possible, as well as their veterinarians. My inquiries for top quality cattlemen in Switzerland to do a selection job for us in the future led me to two persons—Ernst Aegerter, who had for most of his life headed up the export of cattle out of Switzerland, and a Mrs. Ida Hofer, who was a real cattlewoman in her own right, being of a famous cattle breeding family in Switzerland and also married into one.1In a letter to his chidren under date of October 31, 1971, Travers, a deeply religious man who believed in God's governance in the lives of all people, wrote of this experience in selecting Parisien:

[God] led me to the right people in Switzerland, in France, unbeknown to them He influenced men to organize trips for me to see cattle. He gave me ideas and understanding of Cattle and the attendant business far beyond my natural powers. In the past He prepared through mens management of Genetics a Bull that started the biggest revolution for good in the cattle industry on this continent.---------/

1. "Selecting the First Canadian Simmentals," by Travers Smith, Simmemtal Shield, October 1970, pp. 8-10, quote from page 9.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Parisien's Genetics

This chart is on the reverse of a Curtiss Breeding Service Inc., Curtiss Farm, Cary, Illinois promotional sheet for Parisien.

Parisien's Dam

This picture was probably taken sometime between 1968 and 1973. The photographer is unknown.

Uree-Etoile (Parisien's dam), Travers Smith and a French cattleman

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

S.E.P.A. Contract ~ Parisien (August 6, 1966)

Note: there is a prior document also dated 6 August 1966, but unsigned by the parties that shows a "Farm Price" of 15.000 Frs for Parisien and 14.000 Frs each for the alternates, but the price was negogiated upwards to that shown on the signed document. The reasoning is explained in Tavers' letter of Oct. 18, 1966 to be posted hereafter: post title, "1.15: Parisien ~ Payment."

1.10: Finding Parisien (Friday, August 5, 1966)

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

The next 5 days were a whirlwind of activity. Back in Paris by Tuesday morning, August 2, Travers sought out more information on promising herd sites. Both the Swiss cattle people and Canadian Embassy officials directed him to the Pie Rouge (French Simmental) Herd Book at Dijon, France, so by 3 P.M. Tuesday, Travers was in Dijon where the Pie Rouge Cattle Registry people undertook to arrange a tour for the following morning.

There in Dijon at the Herd Registry, Wayne Malmberg, the first Charolais importer, and Ray Woodward, "one of the best Genetists in the U.S." caught up with Travers via telephone. Malmberg and Woodward were in France buying Charolais cattle, but as they had attempted some ground work on the Simmental cattle for Travers, they were interested in meeting him for the Dijon tour along with some of the S.E.P.A men (Societe d'Exportation de Produits Agricoles) of their acquaintance. They recommended tour sites as well. Thus, the next morning (Wednesday, August 3), 2 cars of "Good top men" began a Pie Rouge tour. They travelled 500 miles seeing "good cattle" all along the way. They landed back at Nevers, France that night where Malmberg and Woodward had been staying.

Next day, Thursday, August 4, before Malmberg and Woodward left for Canada, Travers was taken to see some "good Charolais cattle." But by the end of Thursday, Travers still had not seen the Simmental bull calf he was looking for. In the meantime, the Pie Rouge Association secretary had been searching the Association's records to find more unvaccinated cattle of the type Travers desired. The S.E.P.A. men too were making more contacts and on Friday morning, August 5, Travers finally saw the bull he wanted.

Travers’ letter home (Sunday, August 7) does not express his impressions of the 3 unvaccinated bull-calves he selected that Friday, August 5th, but the S.E.P.A. document dated 6 August 1966 shows his first choice as Parisien (No 15.891 c 982, born 16 February 1966), with a farm price of 17.000 Fr. Two alternate choices were required in the event that Parisien failed the health tests. The first alternative, Orkan, was from the Langenieux farm; the second, Oranais, from the Roger farm. First-choice Parisien was from the Henri Rossin farm (C 982) at Saint-Appolinaire, Cote d’Or, only five miles from the Herd Book Office of the Pie Rouge at Dijon.

With the S.E.P.A. documents signed, the animals with their dams were set to enter the requisite testing area on Monday, August 8, 1966, the deadline given by the Canada Department of Agriculture. Travers had beaten the deadline by one day, a Sunday.

First, would came the “on-farm” test and 30-day quarantine. Passing those tests Parisien would be moved on to the quarantine station at Brest, France for more tests and another 30-day quarantine under Canadian control. Passing those tests, Parisien (along with all the Canadian-bound Charolais imports) would be placed on a ship bound for Canada’s quarantine facility at Grosse-Île, Quebec, an island in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

Things were now in process.

The next 5 days were a whirlwind of activity. Back in Paris by Tuesday morning, August 2, Travers sought out more information on promising herd sites. Both the Swiss cattle people and Canadian Embassy officials directed him to the Pie Rouge (French Simmental) Herd Book at Dijon, France, so by 3 P.M. Tuesday, Travers was in Dijon where the Pie Rouge Cattle Registry people undertook to arrange a tour for the following morning.

There in Dijon at the Herd Registry, Wayne Malmberg, the first Charolais importer, and Ray Woodward, "one of the best Genetists in the U.S." caught up with Travers via telephone. Malmberg and Woodward were in France buying Charolais cattle, but as they had attempted some ground work on the Simmental cattle for Travers, they were interested in meeting him for the Dijon tour along with some of the S.E.P.A men (Societe d'Exportation de Produits Agricoles) of their acquaintance. They recommended tour sites as well. Thus, the next morning (Wednesday, August 3), 2 cars of "Good top men" began a Pie Rouge tour. They travelled 500 miles seeing "good cattle" all along the way. They landed back at Nevers, France that night where Malmberg and Woodward had been staying.

Next day, Thursday, August 4, before Malmberg and Woodward left for Canada, Travers was taken to see some "good Charolais cattle." But by the end of Thursday, Travers still had not seen the Simmental bull calf he was looking for. In the meantime, the Pie Rouge Association secretary had been searching the Association's records to find more unvaccinated cattle of the type Travers desired. The S.E.P.A. men too were making more contacts and on Friday morning, August 5, Travers finally saw the bull he wanted.

Travers’ letter home (Sunday, August 7) does not express his impressions of the 3 unvaccinated bull-calves he selected that Friday, August 5th, but the S.E.P.A. document dated 6 August 1966 shows his first choice as Parisien (No 15.891 c 982, born 16 February 1966), with a farm price of 17.000 Fr. Two alternate choices were required in the event that Parisien failed the health tests. The first alternative, Orkan, was from the Langenieux farm; the second, Oranais, from the Roger farm. First-choice Parisien was from the Henri Rossin farm (C 982) at Saint-Appolinaire, Cote d’Or, only five miles from the Herd Book Office of the Pie Rouge at Dijon.

With the S.E.P.A. documents signed, the animals with their dams were set to enter the requisite testing area on Monday, August 8, 1966, the deadline given by the Canada Department of Agriculture. Travers had beaten the deadline by one day, a Sunday.

First, would came the “on-farm” test and 30-day quarantine. Passing those tests Parisien would be moved on to the quarantine station at Brest, France for more tests and another 30-day quarantine under Canadian control. Passing those tests, Parisien (along with all the Canadian-bound Charolais imports) would be placed on a ship bound for Canada’s quarantine facility at Grosse-Île, Quebec, an island in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

Things were now in process.

Monday, May 24, 2010

1.09: "Most Magnificent Cattle"

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

By going to Switzerland first, Travers also hoped to get what advice he could on best selection criteria and farm locations in France from the Swiss. Because of his delayed flight from Paris, the Swiss Cattle Commission offices were closed by the time of his arrival. The next morning (Saturday), he found their offices closed for the weekend, but was finally able to roust a young man in the building to open up to him. The young man was very helpful in arranging for a cattle guide and Travers was soon on his way by train to Spiez to meet his guide to the Simmental (both cattle and valley). His guide was Mrs. Hofer, a middle-aged widow who spoke 5 languages. Her husband had died about five years previous, but as they had raised Simmental Cattle, she “knew all about them, where to go, and the people to see.”

On Saturday, July 30, under the guidance of Mrs. Hofer, Travers got his first view of the best Simmental cattle in the Simmental (the Simme River valley). He described them as “The most Magnificent Cattle I have ever seen.”1

On Monday morning, August 1, Travers left for Geneva, Switzerland arriving about noon where he met a Mr. Roger Decre, an importer and exporter of cattle between Switzerland and France. Travers spent 2-3 hours with Mr. Decre at the Swiss/French border while Mr. Decre cleared cattle. From there they travelled to Mr. Decre's Mountain Ranch near Gex, France looking at cattle all day. By 11 P.M. Travers was back in Geneva, Switzerland, boarding the train for Paris.

---------------

1. Letter to his wife, Belle, July 31, 1966: (BFS-5)

2. Simmental Shield, Oct 1970:8

3. Letter to B.Y. Williams, July 31, 1966: (BYW-2)

By going to Switzerland first, Travers also hoped to get what advice he could on best selection criteria and farm locations in France from the Swiss. Because of his delayed flight from Paris, the Swiss Cattle Commission offices were closed by the time of his arrival. The next morning (Saturday), he found their offices closed for the weekend, but was finally able to roust a young man in the building to open up to him. The young man was very helpful in arranging for a cattle guide and Travers was soon on his way by train to Spiez to meet his guide to the Simmental (both cattle and valley). His guide was Mrs. Hofer, a middle-aged widow who spoke 5 languages. Her husband had died about five years previous, but as they had raised Simmental Cattle, she “knew all about them, where to go, and the people to see.”

On Saturday, July 30, under the guidance of Mrs. Hofer, Travers got his first view of the best Simmental cattle in the Simmental (the Simme River valley). He described them as “The most Magnificent Cattle I have ever seen.”1

I spent some hours with a tape measure measuring these cattle and jotting down the figures and just standing and looking at them. It took some time to pull myself away from this scene.2In his July 31 letter to colleague, B.Y. Williams of Cardston, Travers wrote:

I can’t get over them. We can’t get his kind of animal in 100’s of years of breeding with what we’ve got to work with in Canada. If we can get a few over home it will be the biggest break through for Cattle in a long time. … I’m making every effort and contacted [sic] possible to see if we can’t move cattle from here to France for another year. // … I would sell ½ my herd to get a few of these over.3His plans were to stay in Switzerland till Monday or Tuesday before returning to France to select his import animal, a Red and White Simmental [Pie rouge de l'Est]. On Sunday, July 31, after a morning sick-and-dizzy spell (which he attributed to a delayed vaccination reaction: BFS-5), Travers took time to attend his religious services at the LDS Chapel next to the LDS Swiss Temple. Between church meetings, he visited with one of his new acquaintances, Dr. Winzenried, whose farm was located 1½ miles from the LDS meetinghouse.

On Monday morning, August 1, Travers left for Geneva, Switzerland arriving about noon where he met a Mr. Roger Decre, an importer and exporter of cattle between Switzerland and France. Travers spent 2-3 hours with Mr. Decre at the Swiss/French border while Mr. Decre cleared cattle. From there they travelled to Mr. Decre's Mountain Ranch near Gex, France looking at cattle all day. By 11 P.M. Travers was back in Geneva, Switzerland, boarding the train for Paris.

---------------

1. Letter to his wife, Belle, July 31, 1966: (BFS-5)

2. Simmental Shield, Oct 1970:8

3. Letter to B.Y. Williams, July 31, 1966: (BYW-2)

Saturday, May 22, 2010

1.08: Above the Clouds!

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

After receiving the "permit" news, precious time elapsed before all arrangements were made, but on Wednesday, July 27, 1966 Travers boarded his flight in Lethbridge, Alberta bound for France and Switzerland. He didn’t even have his passport yet, but felt confident he could pick it up during his 5-hour stopover in Ottawa (reduced to 3 hours because of delays). He got his passport without undue complications (crediting his God for “softening the heart of the customs man”) and by Thursday, July 28 at 6:30 P.M., he was waiting in Montreal for his flight to France. In the space of little more than one day, his flight had stopped in Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal.

This was Travers’ first air flight, and mixed in with the thrill of this new experience, he felt a drive that would not let him rest. It was as though his life had been building for this purpose, and that no obstacle could stand against his conviction.

All along his way to Europe, he felt that through God’s providence, he met people who helped him: Dr. Sumption in Lethbridge who “gave me some good advice on Genetics”; a Mr. Russell from Lethbridge travelling to a new government assignment in Charlottetown who, “helped me out a lot”; and “some good leads” for French contacts from the Vets, and from Trades & Commerce in Ottawa. He wrote:

He arrived in Paris, France early Friday morning (July 29, 1966), but only as a stopover. His push was to get to Switzerland.

After a 6-hour unexpected delay in Paris (airline overbooking of flights), he flew on to Zurich and took the train to Bern, arriving Friday night, July 29 at 9 P.M., seven hours later than planned. His determined purpose—to first see the cattle that looked so impressive in the brochures sent by the Swiss Cattle Commission “so that I could compare the animals in France to them.”

---------------

1. Letter to colleague, B.Y. Williams, July 28, 1966: (BYW-1)

2. Letter to his wife, Belle, July 29, 1966: (BFS-4)

After receiving the "permit" news, precious time elapsed before all arrangements were made, but on Wednesday, July 27, 1966 Travers boarded his flight in Lethbridge, Alberta bound for France and Switzerland. He didn’t even have his passport yet, but felt confident he could pick it up during his 5-hour stopover in Ottawa (reduced to 3 hours because of delays). He got his passport without undue complications (crediting his God for “softening the heart of the customs man”) and by Thursday, July 28 at 6:30 P.M., he was waiting in Montreal for his flight to France. In the space of little more than one day, his flight had stopped in Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal.

This was Travers’ first air flight, and mixed in with the thrill of this new experience, he felt a drive that would not let him rest. It was as though his life had been building for this purpose, and that no obstacle could stand against his conviction.

All along his way to Europe, he felt that through God’s providence, he met people who helped him: Dr. Sumption in Lethbridge who “gave me some good advice on Genetics”; a Mr. Russell from Lethbridge travelling to a new government assignment in Charlottetown who, “helped me out a lot”; and “some good leads” for French contacts from the Vets, and from Trades & Commerce in Ottawa. He wrote:

Vets say we may if France cooperates bring cattle from swiss. to calve in France. I'll see if France OKs this.1Travers’ first oceanic flight was

… a most beautiful sight. Billowy mass of cloud below in all shapes high and low like mountains and miles & miles of rolling like pillow cloud[s] … Something I’ve never seen and hard to describe. Has to be seen.2He was like an awe-filled explorer into an unseen, never-imagined world.

He arrived in Paris, France early Friday morning (July 29, 1966), but only as a stopover. His push was to get to Switzerland.

After a 6-hour unexpected delay in Paris (airline overbooking of flights), he flew on to Zurich and took the train to Bern, arriving Friday night, July 29 at 9 P.M., seven hours later than planned. His determined purpose—to first see the cattle that looked so impressive in the brochures sent by the Swiss Cattle Commission “so that I could compare the animals in France to them.”

---------------

1. Letter to colleague, B.Y. Williams, July 28, 1966: (BYW-1)

2. Letter to his wife, Belle, July 29, 1966: (BFS-4)

Friday, May 21, 2010

1.07: Permit ~ At Last!! (CDA - July 7, 1966)

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

Amidst the flurry of continued Simmental research, Travers was anxiously awaiting word on his April 30th request for a permit.1 When the end of June approached, still without word from the CDA, Travers and B.Y. fired off another letter (29 June 1966).1 B.Y. Williams remembered it thus:

------------

1. For copies of these letters to the CDA, see post herein of May 19, 2010.

2. Simmental Shield, March 1974:30

Amidst the flurry of continued Simmental research, Travers was anxiously awaiting word on his April 30th request for a permit.1 When the end of June approached, still without word from the CDA, Travers and B.Y. fired off another letter (29 June 1966).1 B.Y. Williams remembered it thus:

Two days later Travers got a telephone call from Ottawa with apologies and the information that, due to an error, his permit application had been overlooked but had been granted. He had until August 8 to have his calf in farm quarantine in France. Not much time. Five thousand bucks quick, and something to back it up, and a bull required within less than six weeks. We had no problem with money at the time, not having any. We just decided to raise five hundred dollars each and get the same amount from a like number of friends, and we were in business. / Travers had contacted Charley Redd previously and he had said, “If you ever get a permit, I want to pick the bull for you.” So Travers got on the phone. No dice. Charley Redd’s calendar was full. So Travers booked the next suitable reservation he could get for Berne, Switzerland. Switzerland wasn’t open at the time for export, but he wanted a look at the native breed in the country of their origin.2At last, under date of July 7, 1966, Travers received his written permit for the “importation of 1 cattle from France.” He was now in a time squeeze because the Brest, France quarantine was to begin September 1. With the CDA requirement of an approximate 30-day on-farm quarantine before the Brest quarantine, he was informed that the selection had to be made no later than Monday, August 8, 1966.

------------

1. For copies of these letters to the CDA, see post herein of May 19, 2010.

2. Simmental Shield, March 1974:30

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

3rd & 4th Letters to CDA ~ April & June 1966

Letter 3 contains Travers' "application for an import permit effective at the earliest possible date for the number of Red and White Simmental cattle allowed under one permit." Letter 4 is his concerned inquiry that nothing has been heard from the CDA.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

1.06: The Quest Begins

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

Under date of April 4, 1966, Travers sent correspondence to the CDA expressing interest in the "Red and White Simmental" of Switzerland.

When it became apparent that Switzerland was not available for importation purposes, Travers' attention turned to the Simmental cattle that had been imported into France from Switzerland. He was so committed to his Simmental course that in just over three weeks from his first letter to the CDA, he sent his official written request for "the number of Red and White Simmental cattle allowed under one permit … ." The date was April 30, 1966.

Circumstances had forced him to look to France for his "Red and White Simmental," but he never wavered from his idea that Switzerland could be opened for direct importation of the Simmental breed. Such is clearly evident in his early letters to the Commission of Swiss Cattle Breeders' Federation. They, of course, encouraged him in that pursuit.

The more Travers learned, the more driven he became to get this superior breeding stock into North America. He continued his calls and correspondence wherever there was a scrap of hope or information. He was deeply impressed with everything he heard and read. He had a deep sense that Simmental was the breed of the future in North America—that they would take over the country!

Under date of April 4, 1966, Travers sent correspondence to the CDA expressing interest in the "Red and White Simmental" of Switzerland.

When it became apparent that Switzerland was not available for importation purposes, Travers' attention turned to the Simmental cattle that had been imported into France from Switzerland. He was so committed to his Simmental course that in just over three weeks from his first letter to the CDA, he sent his official written request for "the number of Red and White Simmental cattle allowed under one permit … ." The date was April 30, 1966.

Circumstances had forced him to look to France for his "Red and White Simmental," but he never wavered from his idea that Switzerland could be opened for direct importation of the Simmental breed. Such is clearly evident in his early letters to the Commission of Swiss Cattle Breeders' Federation. They, of course, encouraged him in that pursuit.

The more Travers learned, the more driven he became to get this superior breeding stock into North America. He continued his calls and correspondence wherever there was a scrap of hope or information. He was deeply impressed with everything he heard and read. He had a deep sense that Simmental was the breed of the future in North America—that they would take over the country!

Monday, May 17, 2010

1:05: Why Simmental?

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

From Travers' research, the Simmental seemed to have every quality he desired to find. Not only were they a dual purpose animal with excellent milk production and beef quality, but they had a reputation for being docile, having been bred in times past for draft as well as the milk and meat. They had excellent muscling and conformation, and were efficient foragers having developed a hardiness in their native mountain terrain. Their calving weights were reasonable, too, despite the animal's enormous size. In addition, they had reputation for early maturation, high daily gain ratios, longevity, and high fertility. At times, Simmental seemed almost to good to be true.

Travers' first intent was to crossbreed the Simmental with his Herefords. He was used to the solid coloring of Herefords and expected that trait would hold. The white-face of the Simmental was also a pleasing feature to him along with their imposing, fine stature. He anticipated that crossbreeding could produce a cow with milk supply and butterfat content sufficient to dramatically increase the weaning and finishing weight of calves. Genetic-based gainability of calves would also improve.

In short, Travers became converted. What more could one ask than:

---------------

1. These traits would be detailed in a Canadian Simmental Association leaflet about 1969.

From Travers' research, the Simmental seemed to have every quality he desired to find. Not only were they a dual purpose animal with excellent milk production and beef quality, but they had a reputation for being docile, having been bred in times past for draft as well as the milk and meat. They had excellent muscling and conformation, and were efficient foragers having developed a hardiness in their native mountain terrain. Their calving weights were reasonable, too, despite the animal's enormous size. In addition, they had reputation for early maturation, high daily gain ratios, longevity, and high fertility. At times, Simmental seemed almost to good to be true.

Travers' first intent was to crossbreed the Simmental with his Herefords. He was used to the solid coloring of Herefords and expected that trait would hold. The white-face of the Simmental was also a pleasing feature to him along with their imposing, fine stature. He anticipated that crossbreeding could produce a cow with milk supply and butterfat content sufficient to dramatically increase the weaning and finishing weight of calves. Genetic-based gainability of calves would also improve.

In short, Travers became converted. What more could one ask than:

▪ Fertility—Calf every yearThis author remembers hearing Travers suggest during a speech in Great Falls, Montana about 1970 (and not entirely in jest) that the Simmental breed might be descended from Biblical Jacob's "speckled and spotted" superior cattle mentioned in Old Testament Genesis, chapter 30.

▪ Hardiness—Long life

▪ Growthiness—Size for age

▪ Temperament—Quiet and gentle

▪ High milking ability—average butterfat over 4%

▪ Excellent meat carrying conformation1

---------------

1. These traits would be detailed in a Canadian Simmental Association leaflet about 1969.

Saturday, May 15, 2010

1.04: The Simmental Idea

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

[Various articles over the years contain differing versions/memories of founding events relating to Simmental. This writer, referring to letters, accounts, documents, and records preserved by Travers' family, has tried to construct as accurate an account as possible.]

In that first week of January 1966, Travers became distracted from his "Brown Swiss" thoughts after reading Dr. Hobart Peters 1964 Report of travels in Switzerland containing comments on the Simmental breed. This was the first time (January 1966) Travers had heard of Simmental.1 He was immediately taken with what he read, and began to pursue every bit of information he could find about Simmental cattle—calling anyone he thought might know something of the Swiss Simmental. Men like, Hobart Peters of the CDA, Charles Redd of LaSal Utah, Wayne Malmberg, a key-player in the Charolais movement, and others. The more information he gathered, the more enthused he became.

By February 25, 1966 he’d sent his first letter of inquiry to Switzerland. B.Y. (Young) Williams of the Cardston Credit Union, a fellow rancher and a business associate of Travers’ Uncle John S. Smith, became Travers’ sounding board and colleague. Travers would write or tell Young Williams what he wanted to say in his letters to the Commission of Swiss Cattle Breeding Federation and to the Canadian government and Young would type them for Travers’ signature. Those letters (some reproduced herein from carbon copies), set out the early course of events.

The letters to Switzerland took about a five to six week turnaround, so while he eagerly awaited brochures and price information, Travers continued talking up his idea with anyone who would listen.

If he did not already know, from the buzz in the industry concerning the 1965/66 Charolais imports, he soon learned of them and the idea began to form that he could import not only frozen semen (which seems to have been his first thought) but perhaps even Simmental breeding stock.

-----------------

1. BetterBeefBusiness, June-July 1969, p. 11, various writings of Travers, & statements by Travers' wife, Belle.

[Various articles over the years contain differing versions/memories of founding events relating to Simmental. This writer, referring to letters, accounts, documents, and records preserved by Travers' family, has tried to construct as accurate an account as possible.]

In that first week of January 1966, Travers became distracted from his "Brown Swiss" thoughts after reading Dr. Hobart Peters 1964 Report of travels in Switzerland containing comments on the Simmental breed. This was the first time (January 1966) Travers had heard of Simmental.1 He was immediately taken with what he read, and began to pursue every bit of information he could find about Simmental cattle—calling anyone he thought might know something of the Swiss Simmental. Men like, Hobart Peters of the CDA, Charles Redd of LaSal Utah, Wayne Malmberg, a key-player in the Charolais movement, and others. The more information he gathered, the more enthused he became.

By February 25, 1966 he’d sent his first letter of inquiry to Switzerland. B.Y. (Young) Williams of the Cardston Credit Union, a fellow rancher and a business associate of Travers’ Uncle John S. Smith, became Travers’ sounding board and colleague. Travers would write or tell Young Williams what he wanted to say in his letters to the Commission of Swiss Cattle Breeding Federation and to the Canadian government and Young would type them for Travers’ signature. Those letters (some reproduced herein from carbon copies), set out the early course of events.

The letters to Switzerland took about a five to six week turnaround, so while he eagerly awaited brochures and price information, Travers continued talking up his idea with anyone who would listen.

If he did not already know, from the buzz in the industry concerning the 1965/66 Charolais imports, he soon learned of them and the idea began to form that he could import not only frozen semen (which seems to have been his first thought) but perhaps even Simmental breeding stock.

-----------------

1. BetterBeefBusiness, June-July 1969, p. 11, various writings of Travers, & statements by Travers' wife, Belle.

Hobart F. Peters ~ 1964 Report

Scanned images of pages 21-22 of Hobart F. Peters' report "of travels in Europe studying animal breeds in 1964" that Travers read in January 1966 and which began the Simmental adventure.

Friday, May 14, 2010

1.03: Travers Smith ~ Background

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

For many years, Travers Smith of Mountain View, Alberta Canada had sought to improve the performance and profitability of his cattle. The Smith Ranch endeavor, since the days of Travers' grandfather, beginning in 1899, had focused on commercial and purebred Herefords. But like most ranches, the Smith one had suffered its share of down times. The Smith men always considered themselves cattlemen, but they had, in various times of financial crisis turned to sheep and horses to keep afloat. Travers endured his own cycles through sheep and horses (arabians, miniature shetlands, etc.) but always with a few beef cattle on the side, knowing that when things improved, the cattle would become the main focus again.

In the 1950s and early '60s, Travers continued his search for ways to improve his Hereford stock. He felt there had to be increased milk production by mother cows if the daily gain of calves was to be improved, but the divide between beef and milk producing animals had resulted in essentially single purpose animals—either beef or milk, but not both.

Travers was open to innovations and tried crossbreeding and Artificial Insemination (AI) before they were generally accepted practices, but the results, though improved in performance, didn't always have the eye-appeal that the market demanded. Many times it seemed a losing battle.

Travers began looking at purebred animals, with high performance and progeny records to get the improvements he wanted, but the process seemed painfully slow. He believed in the value of record keeping and performance, so he joined the Performance Registry International (PRI) and began putting his own animals to the test. (Some of his Hereford testing was still in process as Simmental began its North American explosion. In 1967-8 and 1968-9 Travers' Hereford Herd Sire produced the highest gaining group of five at the Stanford Progeny Testing station at Stanford, Montana, and at Billings, Montana.)

In the meantime, Travers was always seeking new information wherever he could find it. In the spring of 1965, he received a 2-page report (with letter dated March 29, 1965: reproduced hereafter) from Hobart F. Peters, geneticist with the CDA, Lethbridge Research Branch, detailing crossbreeding results for several breeds. Travers was impressed by the Hereford/Brown Swiss superior performance records and determined to pursue that direction.

In addition, over the winter of 1965-66, he witnessed firsthand in a home-ranch/government-supervised performance test, how a neighbor's ¾ Brown Swiss / ¼ Hereford bull included in the test out-performed his (Travers') good Hereford calves: 878 pounds to 600 pounds at 245 days. Clearly, it was time to make some changes.

(For additional information on performance interests, see posts of May 8 & 10, 2010)

For many years, Travers Smith of Mountain View, Alberta Canada had sought to improve the performance and profitability of his cattle. The Smith Ranch endeavor, since the days of Travers' grandfather, beginning in 1899, had focused on commercial and purebred Herefords. But like most ranches, the Smith one had suffered its share of down times. The Smith men always considered themselves cattlemen, but they had, in various times of financial crisis turned to sheep and horses to keep afloat. Travers endured his own cycles through sheep and horses (arabians, miniature shetlands, etc.) but always with a few beef cattle on the side, knowing that when things improved, the cattle would become the main focus again.

In the 1950s and early '60s, Travers continued his search for ways to improve his Hereford stock. He felt there had to be increased milk production by mother cows if the daily gain of calves was to be improved, but the divide between beef and milk producing animals had resulted in essentially single purpose animals—either beef or milk, but not both.

Travers was open to innovations and tried crossbreeding and Artificial Insemination (AI) before they were generally accepted practices, but the results, though improved in performance, didn't always have the eye-appeal that the market demanded. Many times it seemed a losing battle.

Travers began looking at purebred animals, with high performance and progeny records to get the improvements he wanted, but the process seemed painfully slow. He believed in the value of record keeping and performance, so he joined the Performance Registry International (PRI) and began putting his own animals to the test. (Some of his Hereford testing was still in process as Simmental began its North American explosion. In 1967-8 and 1968-9 Travers' Hereford Herd Sire produced the highest gaining group of five at the Stanford Progeny Testing station at Stanford, Montana, and at Billings, Montana.)

In the meantime, Travers was always seeking new information wherever he could find it. In the spring of 1965, he received a 2-page report (with letter dated March 29, 1965: reproduced hereafter) from Hobart F. Peters, geneticist with the CDA, Lethbridge Research Branch, detailing crossbreeding results for several breeds. Travers was impressed by the Hereford/Brown Swiss superior performance records and determined to pursue that direction.

In addition, over the winter of 1965-66, he witnessed firsthand in a home-ranch/government-supervised performance test, how a neighbor's ¾ Brown Swiss / ¼ Hereford bull included in the test out-performed his (Travers') good Hereford calves: 878 pounds to 600 pounds at 245 days. Clearly, it was time to make some changes.

(For additional information on performance interests, see posts of May 8 & 10, 2010)

Hobart F. Peters ~ 1965 Letter & Report

Scanned images of Hobart F. Peters' March 25, 1965 letter and report sent to Travers Smith which sparked Travers' initial interest in Brown Swiss.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Canada Opens to European Imports ~ 1965

Some relevant, online archived news items & notices from Canadian veterinary journals searched out by SMS:

"Summary of Importation of Livestock into Canada"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 26(4)—April 1962, p. iv: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1583425/pdf/vetsci00065-0002.pdf

"10 Years Ago—[Foot-and-Mouth]"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 26(11)—Nov 1962, p. 275: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1583581/?page=1

"Livestock Import Eased"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 29(2)—Feb 1965, p. 54; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494368/?page=1

"Maximum Security Quarantine Station"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 29(7)—Jul 1965. p. 191: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494426/?page=2

"'Grosse-Ile': an overview of the island's past role in human and animal medicine in Canada" by Thomas W. Dukes; The Canadian Veterinary Journal, Vol. 42(8)–August 2001, pp. 643–648; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1476563/?page=1

"Health Tests Begin on Charolais Cattle"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 29(10)—Oct 1965, p. 266: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494454/?page=1

"Charolais Imports—More on the Way"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 30(4)—April 1966, p. 117: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494523/pdf/vetsci00017-0026.pdf

"The Cattle of the Future"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 31(9)—Sep 1967, p. v; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494725/?page=3

"Canadian Importation of Cattle from Europe"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine, Vol. 32(3)—July 1968; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1319273/pdf/compmed00070-0002.pdf

"Summary of Importation of Livestock into Canada"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 26(4)—April 1962, p. iv: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1583425/pdf/vetsci00065-0002.pdf

"10 Years Ago—[Foot-and-Mouth]"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 26(11)—Nov 1962, p. 275: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1583581/?page=1

"Livestock Import Eased"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 29(2)—Feb 1965, p. 54; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494368/?page=1

"Maximum Security Quarantine Station"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 29(7)—Jul 1965. p. 191: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494426/?page=2

"'Grosse-Ile': an overview of the island's past role in human and animal medicine in Canada" by Thomas W. Dukes; The Canadian Veterinary Journal, Vol. 42(8)–August 2001, pp. 643–648; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1476563/?page=1

"Health Tests Begin on Charolais Cattle"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 29(10)—Oct 1965, p. 266: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494454/?page=1

"Charolais Imports—More on the Way"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 30(4)—April 1966, p. 117: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494523/pdf/vetsci00017-0026.pdf

"The Cattle of the Future"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 31(9)—Sep 1967, p. v; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494725/?page=3

"Canadian Importation of Cattle from Europe"; Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine, Vol. 32(3)—July 1968; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1319273/pdf/compmed00070-0002.pdf

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

1.02: The Importation Process

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

Dr. Ken Well's commitment to safe, direct importation resulted in a complex and comprehensive four-stage testing and quarantine procedure.

At the first stage, importers would select unvaccinated calves from French farms, usually in July. These calves would then be subject to on-farm tests and an on-farm, 30-day quarantine under Canadian control. If they passed the on-farm tests, the calves would be moved on to the second stage—to the Maximum Quarantine Facility that Canada had negotiated the use of at Brest, France. There, the calves would be subject to more tests and another 30-day quarantine, again under Canadian control.

Upon passing this second testing, the imports would be shipped by boat from Brest, France across the Atlantic to a maximum quarantine facility that Canada had established on the small island of Grosse-Ile, Quebec, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This Canadian quarantine station—the third stage of testing and control—was ideally suited in its total isolation from mainland Canada. Here the calves—arriving in the fall—would be subject to a 90-day quarantine and observation period; though, in effect, the quarantine would last well beyond the 90 days because the icebound St. Lawrence did not break up till March or April. When transport became possible, the calves would be shipped by boat, along the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City, where they would be greeted by their anxious importers and shipped by rail to their farm destinations. At their Canadian farms, they would undergo the fourth and final stage—a 90-day on-farm quarantine/observation with a group of indigenous control-cattle. The idea of control cattle (also to be used on Grosse-Ile) was that these controls would have no immunity or resistance to foot-and-mouth and would contract it, if there were any threat being carried by the import.

This four-stage process would prove a rigorous and lengthy procedure, consuming about a year between the time of selection in France to the time the imports received clearance after their Canadian farm quarantine. To most importers the time required must have seemed almost unbearable, but the thorough, clearly defined procedures established by Dr. Wells and his staff, laid an indispensable foundation for all that followed.

In the words of Ted Pritchett,

-----------

1. "Maximum Quarantine" by Ted Pritchett, Simmental Country, August 1987, p. 59. For a more extensive history, see pp. 51, 54-55, 58-59.

2. For a brief history of Grosse-Ile as an animal quarantine and research facility see relevant sections of The Canadian Veterinary Journal, Vol. 42, August 2001, particularly pp. 464-467 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1476563/?page=1

Dr. Ken Well's commitment to safe, direct importation resulted in a complex and comprehensive four-stage testing and quarantine procedure.

At the first stage, importers would select unvaccinated calves from French farms, usually in July. These calves would then be subject to on-farm tests and an on-farm, 30-day quarantine under Canadian control. If they passed the on-farm tests, the calves would be moved on to the second stage—to the Maximum Quarantine Facility that Canada had negotiated the use of at Brest, France. There, the calves would be subject to more tests and another 30-day quarantine, again under Canadian control.

Upon passing this second testing, the imports would be shipped by boat from Brest, France across the Atlantic to a maximum quarantine facility that Canada had established on the small island of Grosse-Ile, Quebec, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This Canadian quarantine station—the third stage of testing and control—was ideally suited in its total isolation from mainland Canada. Here the calves—arriving in the fall—would be subject to a 90-day quarantine and observation period; though, in effect, the quarantine would last well beyond the 90 days because the icebound St. Lawrence did not break up till March or April. When transport became possible, the calves would be shipped by boat, along the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City, where they would be greeted by their anxious importers and shipped by rail to their farm destinations. At their Canadian farms, they would undergo the fourth and final stage—a 90-day on-farm quarantine/observation with a group of indigenous control-cattle. The idea of control cattle (also to be used on Grosse-Ile) was that these controls would have no immunity or resistance to foot-and-mouth and would contract it, if there were any threat being carried by the import.

This four-stage process would prove a rigorous and lengthy procedure, consuming about a year between the time of selection in France to the time the imports received clearance after their Canadian farm quarantine. To most importers the time required must have seemed almost unbearable, but the thorough, clearly defined procedures established by Dr. Wells and his staff, laid an indispensable foundation for all that followed.

In the words of Ted Pritchett,

"the feat [Dr. Wells and his staff] accomplished from an animal health point of view was nothing short of remarkable, but to the public, the introduction of the Continental breeds and their impact on the North American beef industry is beyond description."1As part of the import program the Canadian government undertook to build the required Maximum Quarantine facility of its own at Grosse-Ile,2 Quebec. By 1965 the facility was ready to accommodate 120 head of cattle. Its capacity was expanded in subsequent years as demand escalated.

-----------

1. "Maximum Quarantine" by Ted Pritchett, Simmental Country, August 1987, p. 59. For a more extensive history, see pp. 51, 54-55, 58-59.

2. For a brief history of Grosse-Ile as an animal quarantine and research facility see relevant sections of The Canadian Veterinary Journal, Vol. 42, August 2001, particularly pp. 464-467 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1476563/?page=1

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

1.01: Laying the Foundation ~ The Charolais Advocates

(From Chp. 1 ~ 1966, titled "Foundation Work," in a book begun several years ago by SMSmith to document the early history of SBL and Simmental in North America.)

From the Charolais breeders' point-of-view the import decision by the Canadian Department of Agriculture (CDA) had been long in coming. They had been operating from a purebred base using Charolais cattle imported from Mexico and the U.S. for about 11 years, but now they had hope of new seed stock from France, the native home of Charolais.

In prior years the Canadian government's answer to repeated requests had been to stress the impossibility of direct European importation because of the dreaded foot-and-mouth disease that seemed part and parcel of the European cattle industry at that time.

For many years in Europe, eradication of foot-and-mouth disease was unsuccessful so the focus became control through vaccination. Such was unacceptable to Canadian authorities. The CDA's memory was still fresh with the enormous losses suffered in a 1952 foot-and-mouth outbreak in Saskatchewan. The International Export embargo against Canada at that time had been swift and costly. It was not something the CDA intended to suffer again. Canada would remain free of foot-and-mouth disease at all costs, thus the desire to find exciting new, genetic material was not considered worth the risk of importing a debilitating disease.

But the CDA was also cognizant of the frustrated "back-door" approach that some Charolais breeders were considering to get new breeding stock into Canada. By transporting French Charolais cattle to the French island of St. Pierre, just south of Newfoundland, breeders hoped to somehow get the offspring of these "transports" into Canada legally. At the time, this strategy seemed the most feasible way to approach the Canadian prohibition against direct importation.3

Dr. Ken Wells, Veterinary Director General of the Health of Animals Branch of the CDA, spoke of Canada's import decision to Ted Pritchett of the Simmental Country magazine, August 1987:

In any event, with the Minister's new directive to Dr. Wells, the Canadian government's focus suddenly shifted to the possibilities for direct importation. Fortunately for the cattle industry, Dr. Wells was the proverbial right man in the right place at the right time. His experiences had uniquely prepared him to research and establish—with the help of an able staff—an importation program that would protect the Canadian cattle industry, while at the same time allay the fears of the United States cattle industry.

In the words of Dr. Wells:

-------------

1. "The Simmental Story," by Rodney James, Simmental Country, August, 1987, p. 20, hdnote. (See also, http://data.charolais.com/wordpress/index.php/about-2/history/ ; http://www.ansi.okstate.edu/breeds/cattle/charolais/ . Note however, this Charolais history states 1966/67 as being the first Charolais import year, but other records confirm 1965/66 as the first year. See News and Views: "Charolais Imports — More On the Way" from page 117 of Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 30(4)— April 1966 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494523/?page=1 See also New and Views: "Maximum Security Quarantine Station," Vol. 29(7)—July 1965, pp. 191 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494426/?page=2 ; News and Views: "Health Tests Begin on Charolais Cattle," Vol. 29(10)—October 1965, p. 266 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494454/?page=1

2. For story on "C 15" purchased from Clint Ferris at Tie Siding, Wyoming, see White Gold: The Story of Charolais in Canada by Sharon Henwood and Bonnie Carruthers, pub. by the Canadian Charolais Assoc., 1986, pp. 15-6.

3. For additional information, see "The Simmental Story," by Rodney James, Simmental Country, August, 1987, p. 20, 22, & 24.

4. "Maximum Quarantine" by Ted Pritchett, Simmental Country, August 1987, p. 51.

5. Import years are framed as 1965/66, because the cattle were chosen in France in 1965; subjected to various quarantines there; arrived at Grosse-Ile, Quebec Canada in the late fall of that year for a minimum 90-day quarantine; thereafter released to their importers in the early spring of 1966 for a further on-farm quarantine; and finally released into breeding service, usually early summer. It was virtually a year-long process. See references at footnote 1. above to establish 1965/66 at the first import year.

"The history of all European breeds in North America is irrevocably linked to Charolais because the original decision to allow the import of this breed from France to Canada opened the possibility for every other breed in the years that followed."1Wayne Malmberg (1906-1978) was a southern Alberta cattle rancher who was driven to challenge the commercial status quo of "blocky, compact, fat-producing" cattle. In Malmberg's view, rate of gain and lean meat/fat ratio should be re-evaluated in order to produce better cattle and better profits—the same ideas that would later capture Travers Smith, another southern Alberta rancher, 10 years Malmberg's junior. In his quest for “growthier, vigorous” cattle, Malmberg imported the first Charolais bull (C 15) into Canada from the U.S. in April 1954.2 His search soon led him also to the Charolais cattle of France and to becoming a prime mover and pioneer in pushing to open Canada to European importations. Malmberg and his Charolais associates lobbied for several years, but it was not until 1962 or 1963 that direct importation from France was seriously acted upon.

From the Charolais breeders' point-of-view the import decision by the Canadian Department of Agriculture (CDA) had been long in coming. They had been operating from a purebred base using Charolais cattle imported from Mexico and the U.S. for about 11 years, but now they had hope of new seed stock from France, the native home of Charolais.

In prior years the Canadian government's answer to repeated requests had been to stress the impossibility of direct European importation because of the dreaded foot-and-mouth disease that seemed part and parcel of the European cattle industry at that time.

For many years in Europe, eradication of foot-and-mouth disease was unsuccessful so the focus became control through vaccination. Such was unacceptable to Canadian authorities. The CDA's memory was still fresh with the enormous losses suffered in a 1952 foot-and-mouth outbreak in Saskatchewan. The International Export embargo against Canada at that time had been swift and costly. It was not something the CDA intended to suffer again. Canada would remain free of foot-and-mouth disease at all costs, thus the desire to find exciting new, genetic material was not considered worth the risk of importing a debilitating disease.

But the CDA was also cognizant of the frustrated "back-door" approach that some Charolais breeders were considering to get new breeding stock into Canada. By transporting French Charolais cattle to the French island of St. Pierre, just south of Newfoundland, breeders hoped to somehow get the offspring of these "transports" into Canada legally. At the time, this strategy seemed the most feasible way to approach the Canadian prohibition against direct importation.3

Dr. Ken Wells, Veterinary Director General of the Health of Animals Branch of the CDA, spoke of Canada's import decision to Ted Pritchett of the Simmental Country magazine, August 1987:

"It all began in 1962 when we attended a meeting of the Charolais Association at the Palliser Hotel in Calgary. They were pushing for direct imports from France and Alvin Hamilton, who was the Minister of Agriculture at the time, agreed in principle to look into the feasibility of establishing a Maximum Quarantine Facility for that purpose. I was directed to investigate what we needed in the way of tests and health programs and facilities." (p. 51)Rodney James, "a mover-and-shaker" in the Canadian Charolais Association, recalled that it was during a 1963 visit to France, that The Honorable Harry Hays, Minister of the CDA gave directive to Dr. Ken Wells, Veterinary Director General of Canada, to find a way to open up European importation.

In any event, with the Minister's new directive to Dr. Wells, the Canadian government's focus suddenly shifted to the possibilities for direct importation. Fortunately for the cattle industry, Dr. Wells was the proverbial right man in the right place at the right time. His experiences had uniquely prepared him to research and establish—with the help of an able staff—an importation program that would protect the Canadian cattle industry, while at the same time allay the fears of the United States cattle industry.

In the words of Dr. Wells:

"What followed was an incredible amount of investigation, planning and co-ordination with all the people involved in Foot and Mouth disease. We had to work closely with our counterparts in France, gaining their permission for us to conduct the necessary test, according to our requirements and to negotiate the use of the Brest Quarantine facility in France."4So it was that the efforts of Malmberg and his Charolais associates helped set the stage for the first cattle importations from France in 1965/665 and sparked a revolution in the North American cattle industry. Malmberg became known as "Mr. Charolais of Canada."

-------------

1. "The Simmental Story," by Rodney James, Simmental Country, August, 1987, p. 20, hdnote. (See also, http://data.charolais.com/wordpress/index.php/about-2/history/ ; http://www.ansi.okstate.edu/breeds/cattle/charolais/ . Note however, this Charolais history states 1966/67 as being the first Charolais import year, but other records confirm 1965/66 as the first year. See News and Views: "Charolais Imports — More On the Way" from page 117 of Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 30(4)— April 1966 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494523/?page=1 See also New and Views: "Maximum Security Quarantine Station," Vol. 29(7)—July 1965, pp. 191 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494426/?page=2 ; News and Views: "Health Tests Begin on Charolais Cattle," Vol. 29(10)—October 1965, p. 266 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494454/?page=1

2. For story on "C 15" purchased from Clint Ferris at Tie Siding, Wyoming, see White Gold: The Story of Charolais in Canada by Sharon Henwood and Bonnie Carruthers, pub. by the Canadian Charolais Assoc., 1986, pp. 15-6.

3. For additional information, see "The Simmental Story," by Rodney James, Simmental Country, August, 1987, p. 20, 22, & 24.

4. "Maximum Quarantine" by Ted Pritchett, Simmental Country, August 1987, p. 51.

5. Import years are framed as 1965/66, because the cattle were chosen in France in 1965; subjected to various quarantines there; arrived at Grosse-Ile, Quebec Canada in the late fall of that year for a minimum 90-day quarantine; thereafter released to their importers in the early spring of 1966 for a further on-farm quarantine; and finally released into breeding service, usually early summer. It was virtually a year-long process. See references at footnote 1. above to establish 1965/66 at the first import year.

Monday, May 10, 2010

Travers before Simmental ~ Part Two

In Simmental Country, August 1987, Douglas G. Blair of Western Breeders Service wrote:

With all his new ideas about performance possibilities, Travers began to read and search for the best performing breed. He received information from H.F. Peters, geneticist with the Lethbridge Research Branch of the Canada Department of Agriculture under date of March 29, 1965, showing that in a 1962-63 U.S. experimental test at Miles City, Montana, the Hereford/Brown Swiss cross out-performed in daily gain, every other bred including the newly imported Charolais and Charolais/domestic crossbreds. Travers decided to pursue that course—Hereford/ Brown Swiss crosses. But good cattle cost good money and the banks were often “at the door,” not always impressed with big ideas; so even with all Travers’ dreams, financial realities kept knocking, and knocking loud.

With all his new ideas about performance possibilities, Travers began to read and search for the best performing breed. He received information from H.F. Peters, geneticist with the Lethbridge Research Branch of the Canada Department of Agriculture under date of March 29, 1965, showing that in a 1962-63 U.S. experimental test at Miles City, Montana, the Hereford/Brown Swiss cross out-performed in daily gain, every other bred including the newly imported Charolais and Charolais/domestic crossbreds. Travers decided to pursue that course—Hereford/ Brown Swiss crosses. But good cattle cost good money and the banks were often “at the door,” not always impressed with big ideas; so even with all Travers’ dreams, financial realities kept knocking, and knocking loud.

By mid-1965 things got so bad financially that Travers seriously considered selling his ranch. With six children, born in the space of 10 years (1947-1956), he wondered how he was going to help provide for their college needs and their self-funded, 2-year church missions that he hoped they would all serve for their faith.

With the banks not very inclined to more loans, Travers was stymied as to where to turn to finance this venture with high performance cattle and crosses. He had tried so many ways to clear the ranch debt—that inescapable companion to ranching. He had tried cattle. He had tried sheep. He had tried horses. He seemed to be repeating the frustrating cycle of his fathers’—chasing financial security that seemed always just out of reach. Then, in the first week of January 1966, Travers read a 1964 report by that same Hobart F. Peters, geneticist, about Peters' travels in Europe to study animal breeds, including the Simmental; and with that new information, Travers’ Simmental dream began.

----------

Note: Above news clipping is from an unknown source, probably dated sometime in the mid-1960s.

I used to attend the annual meeting of the Alberta Beef Cattle Performance Test Association and met Travers Smith who was an active member of the organization. Prior to 1967 at the ABCPA meetings he always stressed performance and progeny test information vs. confirmation and showring (p. 106).

With all his new ideas about performance possibilities, Travers began to read and search for the best performing breed. He received information from H.F. Peters, geneticist with the Lethbridge Research Branch of the Canada Department of Agriculture under date of March 29, 1965, showing that in a 1962-63 U.S. experimental test at Miles City, Montana, the Hereford/Brown Swiss cross out-performed in daily gain, every other bred including the newly imported Charolais and Charolais/domestic crossbreds. Travers decided to pursue that course—Hereford/ Brown Swiss crosses. But good cattle cost good money and the banks were often “at the door,” not always impressed with big ideas; so even with all Travers’ dreams, financial realities kept knocking, and knocking loud.

With all his new ideas about performance possibilities, Travers began to read and search for the best performing breed. He received information from H.F. Peters, geneticist with the Lethbridge Research Branch of the Canada Department of Agriculture under date of March 29, 1965, showing that in a 1962-63 U.S. experimental test at Miles City, Montana, the Hereford/Brown Swiss cross out-performed in daily gain, every other bred including the newly imported Charolais and Charolais/domestic crossbreds. Travers decided to pursue that course—Hereford/ Brown Swiss crosses. But good cattle cost good money and the banks were often “at the door,” not always impressed with big ideas; so even with all Travers’ dreams, financial realities kept knocking, and knocking loud.By mid-1965 things got so bad financially that Travers seriously considered selling his ranch. With six children, born in the space of 10 years (1947-1956), he wondered how he was going to help provide for their college needs and their self-funded, 2-year church missions that he hoped they would all serve for their faith.

With the banks not very inclined to more loans, Travers was stymied as to where to turn to finance this venture with high performance cattle and crosses. He had tried so many ways to clear the ranch debt—that inescapable companion to ranching. He had tried cattle. He had tried sheep. He had tried horses. He seemed to be repeating the frustrating cycle of his fathers’—chasing financial security that seemed always just out of reach. Then, in the first week of January 1966, Travers read a 1964 report by that same Hobart F. Peters, geneticist, about Peters' travels in Europe to study animal breeds, including the Simmental; and with that new information, Travers’ Simmental dream began.

----------

Note: Above news clipping is from an unknown source, probably dated sometime in the mid-1960s.

Saturday, May 8, 2010

Travers before Simmental ~ Part One

Like his fathers before him, Travers was interested in obtaining the best cattle he could, and also like his fathers, those cattle were mostly Herefords. When Travers learned of a performance-testing program in the United States he considered it a tremendous idea whose time had come—to improve productivity through performance.

From the Beef Today Yearbook ’77, Fenton Webster1 recalled:

But then Travers was always an innovator. For his herd sire, he went looking for the best performing bull he could find and soon purchased (13 April 1964) a Hereford bull, HH Advance A-326, that was registered with the Performance Registry International as a high performance bull. HH became quite an awesome presence at the ranch in the 1960s.

But then Travers was always an innovator. For his herd sire, he went looking for the best performing bull he could find and soon purchased (13 April 1964) a Hereford bull, HH Advance A-326, that was registered with the Performance Registry International as a high performance bull. HH became quite an awesome presence at the ranch in the 1960s.

From the Beef Today Yearbook ’77, Fenton Webster1 recalled:

Travers was always interested in performance testing, crossbreeding and AI. He really believed that was the coming thing, at a time when none of those ideas were popular or accepted by the cattlemen. Performance testing, to the cattlemen, was still something the college professors played with, and AI, they felt could never be used on the ranches. (BYT’77:78)

But then Travers was always an innovator. For his herd sire, he went looking for the best performing bull he could find and soon purchased (13 April 1964) a Hereford bull, HH Advance A-326, that was registered with the Performance Registry International as a high performance bull. HH became quite an awesome presence at the ranch in the 1960s.

But then Travers was always an innovator. For his herd sire, he went looking for the best performing bull he could find and soon purchased (13 April 1964) a Hereford bull, HH Advance A-326, that was registered with the Performance Registry International as a high performance bull. HH became quite an awesome presence at the ranch in the 1960s.-----------

1. Fenton Webster was a fellow Mountain View Alberta rancher; became an investor and subsequent shareholder in SBL.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)